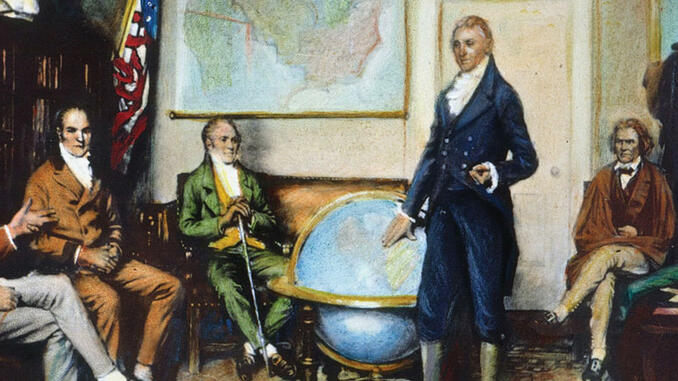

Until the Monroe Doctrine was proclaimed, America had chosen to stay clear of the power struggles between the nations of Europe with what amounted to an isolationist foreign policy. Content in not become with European struggles, America focused its efforts on its own part of the globe. It used the occasion of Spain’s military incursions in Latin America to set the stage of keeping Europe out of the Western Hemisphere. On December 2, 1823, in his seventh address to Congress, President James Monroe made clear a new foreign policy that would later become known as the Monroe Doctrine. It has been the cornerstone of American foreign policy in the Western Hemisphere ever since.

What the Monroe Doctrine essentially established was a moat around America and warned the European colonial powers to stay out. President Monroe declared any European power that “extended their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.” What is remarkable about the Monroe Doctrine is not only did it declare the areas immediately bordering the country as its sphere of influence, but it grandly claimed the whole hemisphere as her sphere of influence.

In the beginning the address was met with disregard and skepticism. Prince Metternich of Austria was angered by the statement, privately writing that it was a “new act of revolt” by the United States and would give “new strength to the apostles of sedition and reanimate the courage of every conspirator.” Britain, having positioned itself against the Holy Alliance which was trying re-establish Bourbon rule in Spain and therefore the colonies in South America, however, indicated it would help enforce the Monroe Doctrine with the Royal Navy. And Latin America with its emancipation movement leaders—Bolívar, Santander, Rivadavia, and Victoria—reacted favorably to the doctrine though with an eye on the fact America did not have a military strong enough to easily enforce its new foreign policy stance. Even up to the 1880’s America’s navy was smaller than those of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile.

Slowly, the interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine was broadened by American presidents. In 1845 President James Polk used the principals of the doctrine to incorporate Texas into the Union. He justified his action by expressing fear that an independent Texas as a nation might become an ally to a European power, and therefore become, by proxy, a European threat to the United States.

By the beginning of the twentieth century America had grown into an industrial power with a strong military and was the supreme power in the Western Hemisphere. Teddy Roosevelt’s further broadened the interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine to include what he called a “corollary” interpreting a more interventionist role. He proclaimed in December of 1904 that because “…in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrong-doing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.” He used this interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine to justify both his former and future actions in Santo Domingo, Nicaragua, Haiti, Panama, and Cuba.

With the outbreak of World War II and America’s emergence to shape the world stage, Woodrow Wilson expressed his vision for the League of Nations by applying the concepts behind the Monroe Doctrine to his vision of organization:

I am proposing as it were, that the nations should with one accord adopt the doctrine of President Monroe as the doctrine of the world. That no nation should seek to extend its polity over any other nation or people…. That all nations henceforth avoid entangling alliances which would draw them into competitions of power…

The Monroe Doctrine entered the nuclear age when in 1962 John F. Kennedy used it when the Soviet Union was discovered assembling nuclear missiles in Cuba. In his televised address Kennedy starkly stated, “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.”

The Monroe Doctrine was a turning point in the history of American foreign policy and how it viewed its role in the world. To understand America’s approach to foreign policy, one cannot go without studying the Monroe Doctrine.

The text of what became known as the Monroe Doctrine:

…At the proposal of the Russian Imperial Government, made through the minister of the Emperor residing here, a full power and instructions have been transmitted to the minister of the United States at St. Petersburg to arrange by amicable negotiation the respective rights and interests of the two nations on the northwest coast of this continent. A similar proposal has been made by His Imperial Majesty to the Government of Great Britain, which has likewise been acceded to. The Government of the United States has been desirous by this friendly proceeding of manifesting the great value which they have invariably attached to the friendship of the Emperor and their solicitude to cultivate the best understanding with his Government. In the discussions to which this interest has given rise and in the arrangements by which they may terminate the occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers…

It was stated at the commencement of the last session that a great effort was then making in Spain and Portugal to improve the condition of the people of those countries, and that it appeared to be conducted with extraordinary moderation. It need scarcely be remarked that the results have been so far very different from what was then anticipated. Of events in that quarter of the globe, with which we have so much intercourse and from which we derive our origin, we have always been anxious and interested spectators. The citizens of the United States cherish sentiments the most friendly in favor of the liberty and happiness of their fellow-men on that side of the Atlantic. In the wars of the European powers in matters relating to themselves we have never taken any part, nor does it comport with our policy to do so. It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we are of necessity more immediately connected, and by causes which must be obvious to all enlightened and impartial observers. The political system of the allied powers is essentially different in this respect from that of America. This difference proceeds from that which exists in their respective Governments; and to the defense of our own, which has been achieved by the loss of so much blood and treasure, and matured by the wisdom of their most enlightened citizens, and under which we have enjoyed unexampled felicity, this whole nation is devoted. We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere. But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintain it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States. In the war between those new Governments and Spain we declared our neutrality at the time of their recognition, and to this we have adhered, and shall continue to adhere, provided no change shall occur which, in the judgement of the competent authorities of this Government, shall make a corresponding change on the part of the United States indispensable to their security.

The late events in Spain and Portugal shew that Europe is still unsettled. Of this important fact no stronger proof can be adduced than that the allied powers should have thought it proper, on any principle satisfactory to themselves, to have interposed by force in the internal concerns of Spain. To what extent such interposition may be carried, on the same principle, is a question in which all independent powers whose governments differ from theirs are interested, even those most remote, and surely none of them more so than the United States. Our policy in regard to Europe, which was adopted at an early stage of the wars which have so long agitated that quarter of the globe, nevertheless remains the same, which is, not to interfere in the internal concerns of any of its powers; to consider the government de facto as the legitimate government for us; to cultivate friendly relations with it, and to preserve those relations by a frank, firm, and manly policy, meeting in all instances the just claims of every power, submitting to injuries from none. But in regard to those continents circumstances are eminently and conspicuously different.

It is impossible that the allied powers should extend their political system to any portion of either continent without endangering our peace and happiness; nor can anyone believe that our southern brethren, if left to themselves, would adopt it of their own accord. It is equally impossible, therefore, that we should behold such interposition in any form with indifference. If we look to the comparative strength and resources of Spain and those new Governments, and their distance from each other, it must be obvious that she can never subdue them. It is still the true policy of the United States to leave the parties to themselves, in hope that other powers will pursue the same course….