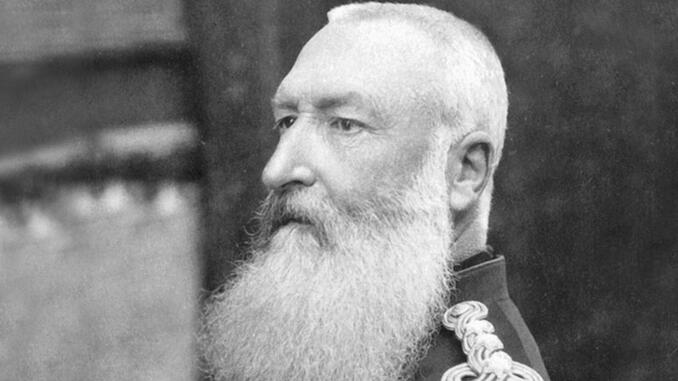

King Leopold II of Belgium is remembered in history as a monster. His atrocities in the Congo committed in the name of greed are the darkest chapters of European colonialism. Through the period from the 1880’s to the 1920’s millions of Africans were killed in the pursuit of profits for Leopold himself. However, during most of this time, most of the world admired him for what they thought to be his noble and “civilizing” mission in Africa. Viscount Ferdinand de Lesseps, who built the Suez Canal, called Leopold “the greatest humanitarian” of his time. It was not until near the end of his life that the world began to notice the true nature of his activities in the Congo.

Leopold’s views of Africa were not much different than those of his contemporaries. Africa at the time was seen by Europeans as “an expanse of empty space waiting to be filled by the cities and railway lines constructed through the magic of European industry,” writes Adam Hochschild in his book “King Leopold’s Ghost.” But it was Leopold’s sheer greed that set him apart. The Congo became his own personal fiefdom where he could exercise more power than he could as the ruler of Belgium itself. In pursuit of increasing his own personal wealth, which he hid from his own country, he let the darkest parts of human behavior drive profits over respect for human beings. In other words, he treated Africans as if they were animals.

In the beginning greed for ivory drove colonialization of the Congo. The Congo River was the main source of transporting goods from the interior of the Congo to the ocean where goods like ivory could then be shipped to Europe. However, just over 230 miles of the river were rapids and rocky gorges that were unnavigable by boat. For those 230 miles goods had to offloaded from steamships and carried by hand around the rapids where the goods were then reloaded on new boats to make the rest of the journey to market. For the task of transporting the goods by hand, porters were needed by imperially chartered companies. To gain porters locals were used, and when demand exceeded the amount of locals willing to work, brutal tactics were used.

European men hired by companies would actively kidnap local villagers and use them as slaves. The slaves were lined up and chained by the necks and marched to the portage trails. The work was back breaking as the slaves carried ivory and other goods on their backs and on their heads for many miles a day with little food and water. Slaves often died from being overworked. If they protested or failed to work efficiently enough they were whipped with strips of hippopotamus hide called a chicotte which easily ripped flesh as if it were paper. Even though slaves were used, Leopold II promoted himself and Belgium as being anti-slavery. Belgium had by this point abolished slavery, but that did not stop the king from using it to increase his personal wealth.

When uses for rubber were realized it created an insatiable demand for the substance which had to be collected from rubber plants. Rubber plants were plentiful in the Congo and a new industry arose. To get rubber, rubber plant vines had to found in the wild and tapped to drain the rubber from them. The work could be brutal.

Again, finding enough workers to meet demand was an issue. Often whole villages would refuse to work and they were summarily massacred by white workers. Rewards were given out for each African refusing work that was killed. To collect the reward, the right hands of the victims were chopped off and collected to be turned in as proof. A Presbyterian missionary by the name of William Sheppard once came across a brutal scene during one of trips to the Congo. He came across a pile of right hands, 81 he counted, being prepared to be turned in to receive the reward money. He wrote about the scene and worked along with others to unveil to the rest of the world the horrors that were taking place in Leopold II’s Congo.

Villagers came to avoid the white men and when they would show up to their villages the locals would flee and hide in the jungles and hills. The white men would then steal the food that was left in the villages and wait until the villagers would starve, forcing them to come back to the villages for food. Women and children were then captured and held hostage. The men would then be forced to work and collect quotas of rubber in order to gain their wives and children back. If they refused they were shot and killed—their right hands would be collected.

Over the decades the horrors in the Congo did leak out to the rest of the world through people like William Sheppard. When Leopold was confronted with allegations of the horrors he and his people would lie and downplay the allegations. Once, when a story about the amputation of hands was made public, a cover story was put out that the victims were suffering from disease. They “were unfortunate individuals, suffering from cancer of the hands, whose hands thus had to be cut off as a simple surgical operation,” said one response in La Tribune Congolaise, a pro-business interest paper. With the help of the British and the Americans, publicity was launched that lead to investigations of the claims of atrocities. Eventually, the claims would be shown to be true.

King Leopold II eventually died in 1909 and slowly the horrors in the Congo began to abate. But to this day, many Belgians are unfamiliar with the atrocities committed under King Leopold II in the Congo. For the ones who do know about that part of their history, It is a history they wish to forget. For many years the government covered up and hid from the public the findings from investigations of what happened. It is estimated that during Leopold’s exploitation of the Congo the population was reduced by 50 percent, or an estimated 10 million people. His earnings during that time are staggering. It is estimated he earned 220 million francs, or the modern equivalent of $1.1 billion. It was the definition of blood money.