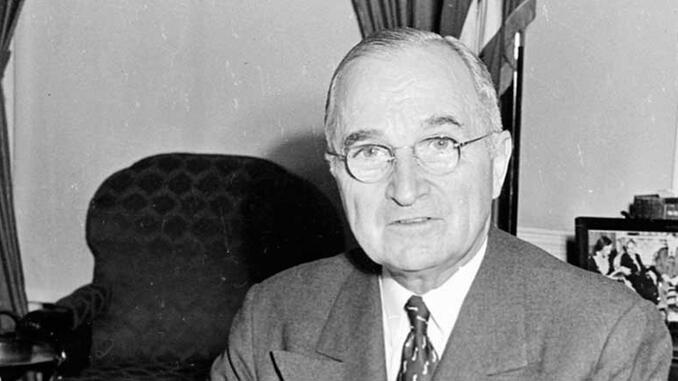

On August 6th, 1945, President Harry Truman was on board the USS Augusta off the coast of England. Just before noon as he sat down for lunch, he was handed a map of Japan with a city circled with a red pen. Attached was a decoded message from his Secretary of War. “Results clear-cut successful in all respects. Visible effects greater than in any test,” the note read.

A few minutes later, just past noon, another note arrived for the President. “Big bomb dropped on Hiroshima August 5 at 7:15 P.M. Washington time. First reports indicate complete success which was even more conspicuous than earlier test.” Thus the preliminary results of one the most difficult decisions that has ever fallen on an American President became known to him. The world would never be the same. How did President Truman decide to use the deadliest weapon every unleashed in war?

Three options were considered before deciding to drop the bomb: conventional bombing of the Japanese home islands, ground invasion of the Japanese home islands, and demonstration of the atomic bomb on an unpopulated area.

America had been bombing the mainland of Japan since 1942. Between spring of 1944 and the end of summer 1945 U.S. bombing raids were estimated to have killed 333,000 civilians and wounded nearly half a million more. The infamous firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945 alone killed 80,000 civilians. Truman noted that even with a bombing as severe as the Tokyo firebombing, Japan still refused to surrender. More than traditional airpower alone was needed to defeat Japan.

Launching a ground invasion of Japanese homeland islands and the mainland also showed the Japanese would not surrender easily and many civilians would be killed. Based on past trends fighting the Japanese, there would be many U.S. soldiers killed and wounded. The 1945 battle of Iwo Jima killed 6,200 servicemen. Later that year, 13,000 U.S. men were killed in the battle of Okinawa. One-third of the American forces that fought in that battle were killed or wounded. With rates that high, Truman was afraid that an invasion of Japan itself would kill and wound millions of servicemen.

With air raids being unable to push Japan towards a surrender, and a ground invasion on the Japanese homeland being a very deadly ordeal for American fighters, another option considered was a demonstration of an atomic blast on an unpopulated area. It was hoped that by doing this the demonstration would scare Japan into surrendering. But there were sobering questions about who Japan would use to witness the atomic explosions. And would Japan surrender on the advice of a single person or small group? Those questions assumed the bomb would work in the first place. It was still experimental and not clearly understood. Not only that, the U.S. only had two atomic bombs. More were in production, but using half the arsenal on a demonstration was a risk.

In May 1945, Truman had formed the Interim Committee to debate the issues behind using the atomic bomb. After a thorough debate the Committee gave their conclusion to the president: “We can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war. We can see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.”

With the decision made to drop the bomb, the next consideration was on where to drop it. Truman and his advisers determined that for best effect upon the enemy, the target had to be a city to maximize the impression. When choosing the city, it was preferred the city did not have much damage from previous attacks so that the Japanese could not argue the damage had come from something else other than a new super-weapon. Also, it was important that the city supported a major military industrial complex and not be a place of major cultural significance. With these factors considered, the city of Hiroshima was picked. There would be no warning of the atomic attack so the Japanese would not have time to prepare and risk the lives of the bombing crew.

When the bomb was finally dropped on Hiroshima some 70,000 to 80,000 people lay dead. Of that number, 20,000 were Japanese soldiers, and another 20,000 were Korean slave laborers. The rest were civilians. An estimated 70,000 were injured. These numbers are only estimates—the exact numbers will never be known because of the extensive damage from the blast.

The day after the Hiroshima bomb was dropped Senator Richard B. Russell of Georgia sent Truman a bellicose telegram to encourage using the bomb repeatedly on Japan. Truman replied to the telegram saying, “I know that Japan is a terribly cruel and uncivilized nation in warfare but I can’t bring myself to believe that because they are beasts, we should ourselves act in that same manner. For myself I certainly regret the necessity of wiping out whole populations because of the ‘pigheadedness’ of the leaders of a nation, and, for your information, I am not going to do it unless absolutely necessary.”

It would take one more bomb to bring Japan to surrender and bring an end to the deadliest war in human history. No president since has been forced to make a decision to use an atomic bomb.